AI has highlighted is how tenuously connected our grasp on reality is. It becomes more tenuous the further away from your experience you go.

Have you ever heard the fact that if I were to unribbon your blood vessels and stretch them around the world, they’d do so twice? It’s the kind of urbane trivia I used to disgorge at high school to amaze and preen, a bit like the myth that Marilyn Manson got his ribcage removed so he could suck his own dick at a concert (a myth, by the way, started and miraculously circulated around the entire western sphere’s high schools without the aid of the internet, an incredible feat of rumor and teenage immaturity). Turns out, the blood vessel fact is bullshit too. My favorite YouTube channel did a whole deep dive on it:

The thing is, most of our world is built on abstract ideas we receive second hand, not unlike the blood vessel tidbit. Frequently, I find myself typing this blog out and referencing obscure facts and stories that fly out of my brain higgelty-piggelty, down through my fingers helter-skelter. I fact check what I write, and I’m frequently dismayed by what turns out to be bullshit; just three weeks ago, I wrote a piece that referenced the story that Henry Stimson redirected the atomic bomb to Hiroshima from Kyoto because he had his honeymoon there. I got this story from two sources: The book Fluke, by Dr Brian Klaas, and Oppenheimer, where it’s referenced by Stimson’s character directly. This felt, to me, like a totally reasonable basis to include the story, especially because it beautifully illustrated my point about a contingent and complex reality.

Turns out there’s no reliable basis for the honeymoon story either. In fact, I ended up including the anecdote, but pared it down to a more anodyne description of a “site-seeing” trip, which itself is based on a sparse diary entry (in which Stimson does refer to his time in Kyoto as “lovely” and “beautiful”). I only caught this because I wanted more details about his trip, looked it up, and found a lengthy blog parsing over the available evidence for the honeymoon story (conclusion: unlikely!). I don’t want to add to the cacophony AI is already firing at the infosphere - more than half of the internet is already just bots bleeping at each other.

A brief anecdote to illustrate the quicksand we’re sinking into. A couple of weeks ago I spilt a cup of boiling water on my crotch. I yelped and yanked my pants off before spending 15 minutes in a cold shower. Fragile in mind and groin, I Googled to see if I needed further medical attention. The AI summary helpfully suggested I immediately go to the ER, which raised my pulse until I checked the source and found it was referencing research that showed most groin burns were associated with serious, whole-body burns. Well, duh - people usually aren’t stupid enough to spill a cuppa on their balls. AI had correctly summarised the research and incorrectly applied it to my… situation. Later that week I Googled if it was safe to go to a sauna (I was healing, but cautious). AI told me it wasn’t safe…referencing an Instagram post that had no likes, an AI-generated caption, and made a passing reference to the fact you might get burned in a sauna if you touch the rocks. C’mon dude.

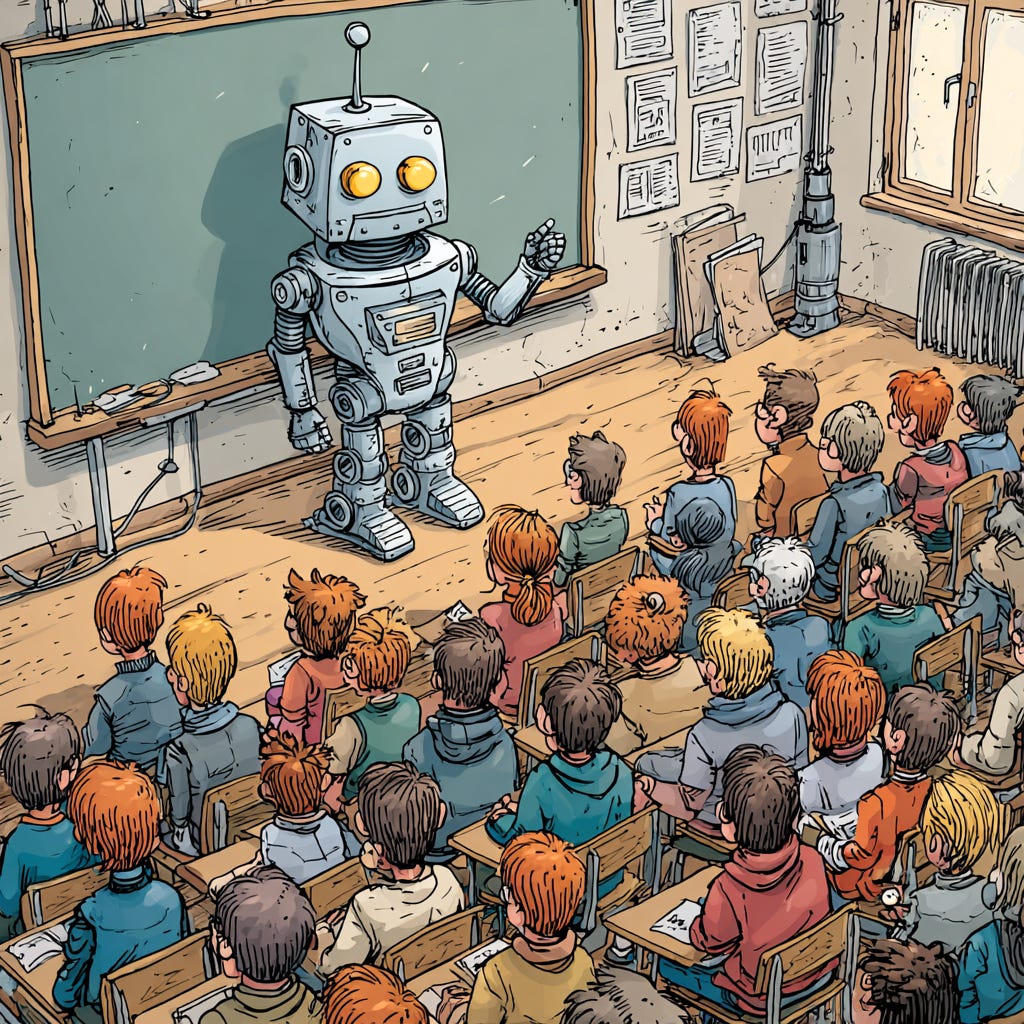

The consequence of this has to involve a paring-back of epistemic humility. We actually have to work patiently through information, to sift among the data points and reference trails for the truth. “Research” no longer means finding facts. Any asshole can find a fact. When facts were precious rarities stuffed away in libraries, and science belonged to an aristocratic class with the time to them, facts stood on their own two legs, triumphant products of humanity’s finest minds and generations of experimentation. Information’s relative scarcity put a premium on it. Now, facts are the diahorrea of the internet, pouring into the fun-house river of bullshittery we call discourse.

Availability of information doesn’t necessarily translate to saner discourse. This is the rudest awakening of the twenty-10s. The information firehose has conspired to make reality feel weirdly distant, where no one - the media, politicians, influencers, the faces on our messenger apps - feels particularly real. The currency of a fact has plummeted in accordance with its ease of summons, because counterveiling ones can be plucked with just as much ease. We note, with rising despondency, just how relative truth appears to be online, how immune to facts identities are, how easily weaponised pluralism has become. When Ben Shapiro smugly said that facts don’t care about your feelings, he was dead wrong. Facts care desperately about feelings, because it is feelings that produce the facts, not the other way around. There’s something else going on here.

We’re thirsty for real. We’re hungry for reality. There’s an aching pit in our stomachs for the really-real, the unignorable kind of truth you can touch but seems like a phantom in the digital, and which facts increasingly make a mockery of. There’s been a lot of recent criticism about the academy’s embrace of an aesthetic movement called ‘postmodernism’. If you’ve come across the Trump administration’s attack on ‘woke’ college discourse, postmodernism is the philosophical root they’re trying to gauge out, emerging in the mid-twentieth century out of the rubble of World War II. Postmodern critics believe the meaning of words is arbitrary, that truth is entirely subjective, the world turning on power games, reality itself wafer-thin. The irony, of course, is that the political right has become as postmodern as the wokes they take aim at. When reality becomes fodder for subjective truth, it turns into thin gruel. Unfortunately, the digital world - brilliant at copy and pasting context-free information - is very, very good at building a postmodern world.

Reality hunger - a phrase I’ve shamelessly stolen from David Shields - isn’t for more information about it. It’s about the endless eroding away of a shared sense of meaning, the pining for the really-real, the truer-than-true.