“People are generally correct in what they assert, and wrong in what they deny.”

- John Stuart Mills

You would think that a discovery as revolutionary and far-reaching as the germ theory of disease - a theory so transformative to society that we cannot conceive what life would be like without it - would have its chief founder spoken of in the same whisper as Einstein or Newton. Yet Ignaz Semmelweis finished his life bereft of fame, full of discontent, despairing in an asylum as his life’s work languished as a curiosity in the medical establishment.

In the mid-1800s, childbirth was a horrifyingly dangerous procedure. As many as one in ten women would enter the maternity ward Semmelweiss worked in and die, the insides of their bodies laden with pustules. The prevailing theory was that the air was responsible, called miasma, with doctors convinced the disease - called childbed fever - stole into maternity wards through the vents. A young doctor named Semmelweiss observed that many of the women who died did so after a doctor had come from handling cadavers and wondered if the two were linked.

He was especially curious why his ward, which had medical students delivering children shortly after slicing up corpses, had higher death rates than a nearby ward which only had dedicated midwives. His eureka moment (although hardly a happy occasion) occurred when his friend was cut while dissecting a corpse, and died shortly after filled with pustules. Semmelweiss theorized it was because of particles found on the bodies, and instituted a hand-cleaning regime in his ward. The results were dramatic, with mortality dropping from 18% to 2%:

You would think such a discovery, so obvious in its results and revolutionary in what it suggested, would sweep the world by storm. But, no - it turns out doctors didn’t like being told their hands were infected, and demanded more evidence from Semmelweiss. People don’t like change.

Semmelweiss was understandably upset by this cold reception, but at this crucial moment he chose to stay silent. When his discovery was first circulated (mostly by his students and second hand accounts), he published nothing to support it, expecting his work to do the talking. When the medical establishment misinterpreted his findings, he railed against their stupidity. His diatribes against his colleagues eventually got him kicked out of his Viennese college, and he returned to Budapest a misunderstood obscurity. He published his main work 13 years after his exile from Vienna, lamenting

"Most medical lecture halls continue to resound with lectures on epidemic childbed fever and with discourses against my theories. In published medical works my teachings are either ignored or attacked. The medical faculty at Würzburg awarded a prize to a monograph written in 1859 in which my teachings were rejected.”

He died in a mental asylum in 1865, after devolving into humiliation, rage and alcoholism.

Accepting the Unacceptable

Your most cherished beliefs will one day be considered crazy artefacts of a less-enlightened society. You have inherited, at no effort, the germ theory of disease and reap the many benefits knowing that tiny organisms floating through the air and lurking on surfaces can make you sick. You have probably never entertained the possibility that “bad air” floats around making people ill, because that’s batshit. The problem is that you also believe in a lot of “bad air” theories yet to be disproved. You probably don’t appreciate it when someone tries to tell you that, either.

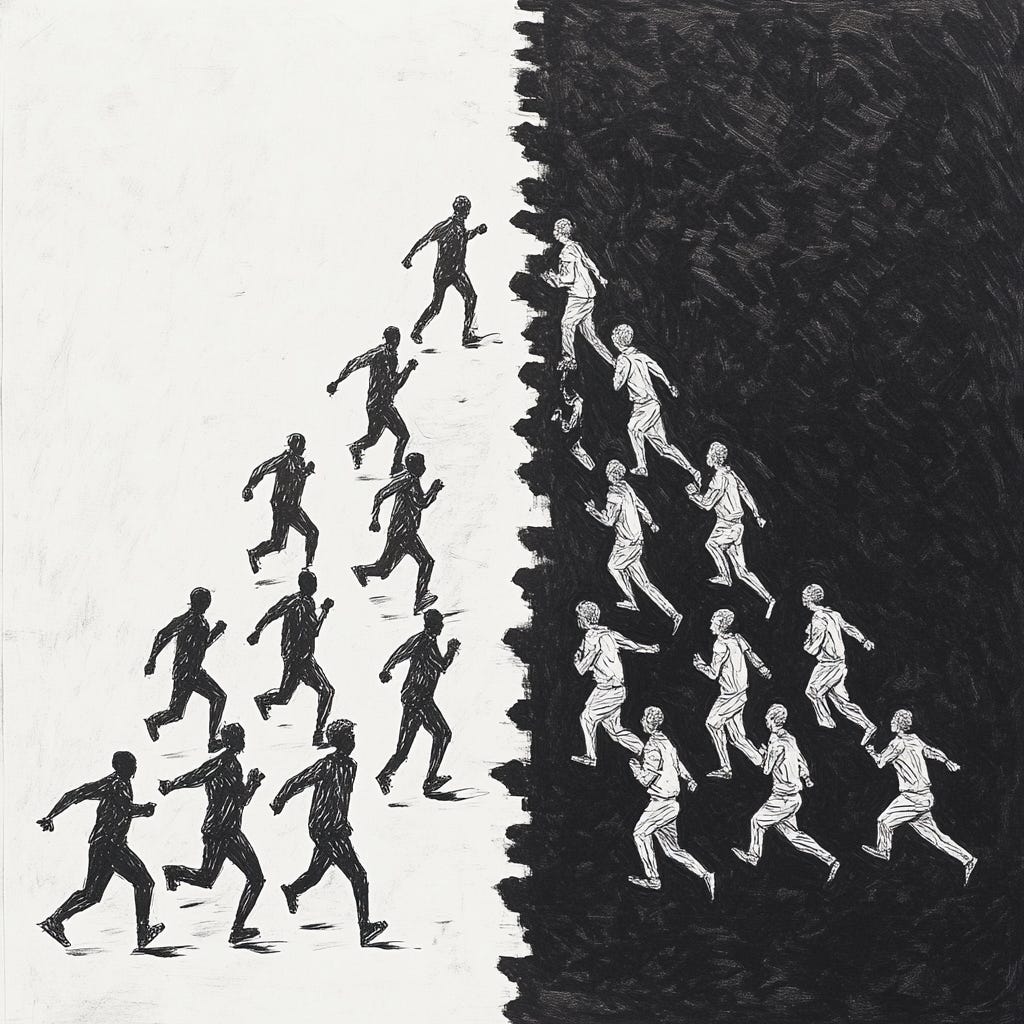

That’s the rub. Semmelweiss went insane because he didn’t realise how hard it is to change people’s minds because facts care desperately about people’s feelings. One of the more momentous findings in social psychology, I believe, is the discovery that we do not form based on facts or concrete truths. No one does, including you and me, regardless of your political and moral beliefs. Instead, we have natural inclinations that we defend like lawyers, pulling at facts to defend a moral construct. It turns out that if you actually do change people’s minds, it’s kind of a miracle.

Because basically no one changes their minds about issues - certainly not in ways that are significant - we can see why making actual, substantive change is hard. Super hard. Call it the price of giving people individual liberty. To do so requires what Vitalik Buterin calls “legitimacy”, or the aura/force people and institutions possess that impells people to do anything at all:

Legitimacy is a pattern of higher-order acceptance. An outcome in some social context is legitimate if the people in that social context broadly accept and play their part in enacting that outcome, and each individual person does so because they expect everyone else to do the same.

That is a tall order, and dispiriting when you really do want to make change in the world. No wonder authoritarianism is so tempting; you get to short-circuit the consensus building and win legitimacy through brute force! Coalitions, while very democratic, are so bloody slow.

For that reason, my recommendation to change makers is simple; keep your audience and ambitions for change modest, at least to start. Let’s finish by looking at legitimacy done right.

Tactical Brown-Nosing

To the most illustrious and invincible Monarch CHARLS, King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, Defender of the Faith.

Most gracious King,

The heart of creatures is the foundation of life, the prince of all, the Sun of their Microcosm, on which all vegetation does depend, from whence all vigor and strength does flow. Likewise the King is the foundation of his Kingdom, and the Sun of his microcosm, the Heart of his Commonwealth, from whence all power and mercy proceeds…

I don’t have the energy to finish typing out the remainder of William Harvey’s dedication to King Charles, on the publication of The Anatomical Exercises of Doctor William Harvey Professor of Physic and Physician to the King’s Majesty, Concerning the Motion of the Heart and Blood. Truly sickening. Times have changed a little; my boss would probably raise an eyebrow if I began our weekly meeting by calling him ‘gracious’.

Yet the book in question is arguably the most important published in medical history. It proposed, for the first time, that the heart pumped blood around the body and organs, rather than producing it for the body to consume - the prevailing theory of the day. Where Semmelweiss told no one about the changes in his ward, Harvey invited scientists over to his house to observe vivisections on dogs and measure the volume of blood circulated in an hour versus the heart’s capacity, proving that the heart did not produce it.

He also invited members of the Royal Society to observe experiments that blood circulated through two separate loops - the pulminory and systemic - and showed that blood could only move one way through a vein thanks to the body’s valves. He brought the entire society of scientists along on the ride, before collecting his findings in the aforementioned book. Upon its release, Harvey not only invented physiology and experimental medicine but ensured they would be accepted by the broader community - the king’s dedication a slimey but necessary exclamation mark on his labor’s fruition.

Harvey also believed in witches, and that Europeans didn’t know how to govern their wives. Those “bad airs” took a little longer to clear.

Share this post