During a particularly sad episode in my life a few years ago, I found myself back at my parent’s house one summer, figuring out what to do with my life as the long Tasmanian summer drew to a golden close. Part of this regression involved rewatching childhood cartoons, especially Avatar, The Last Airbender. If you haven’t seen it, don’t worry. All you need to know is the clip below struck such a chord with me that I immediately wrote the first draft of what follows.

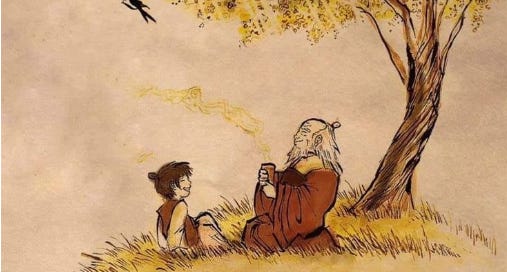

To set the scene, watch this clip to know what healthy masculine role models look like:

Still gets me. What a show. Now, indulge me fanboying over my favorite character in the series as we unpack it.

The Tale of Uncle Iroh’s poignancy stems from that last scene; we learn that all the while, as this cheerful, wise buffoon helps young men around the city, it is the anniversary of his deceased son’s birthday. His deeds suddenly make sense, Iroh returning to his fatherly role to guide the lost and confused (and does so throughout the series with his nephew, Zuko). It’s heartbreaking because we realise Uncle Iroh has retained the mantle of father, which was gifted to him by his son and still alive after his death.

Boys need fathers, and struggle more than their sisters without a positive male role model. To me, male role models don’t just personify classically ‘masculine’ traits like discipline and strength; they understand that good deeds and service to others are a form of resisting entropy. When I transmit an idea or sentiment to you, you receive it with no lessening to either of us. Actually to the contrary; this tiny energetic exchange can occasion possibility, the opportunity to improve ourselves or the world around us with the idea or feeling.

Generous acts are therefore highly asymetrical events. They fortify and expand the givers’ sense of self, and create new possibilities for the receiver. Service and giving capture that mercurial state of improvement, where value flows freely without condition or cost. We see this most clearly when Iroh disarms his assailant trying to mug him, changing the man’s self-conception and improving the world in a stroke.

An immature mind sees service to others as a sacrifice. I wouldn’t blame the bloke if Iroh chose to stay in bed all day on his son’s birthday. Life is hard, and we all have to deal with its flipside - death - every day. It’s perfectly natural, even understandable, to shrink in the face of bullshit the world is capable of summoning against us. To me, healthy masculinity shows up despite this inevitability. Uncle Iroh refuses to have his nature, his truth dictated by death. If anything, it is death’s presence that makes him show up for his surrogates, widening his circle of concern and compassion.

It’s hard to maintain Iroh’s expansive state. Reading a harrowing passage from Andrew Solomon’s The Noonday Demon, he describes how depression feels like a narrowing. Pleasures become narrowed to a few, scant activities; the world narrows to your dullness and numbness; your consciousness narrows to basic things, like getting out of bed to have a shower. Your horizons shrink. We don’t become self-obsessed so much as we’re reduced to merely our suffering. Our ego, with its neurosis and memories, replays stories in our heads to explain what’s happening in terms we can understand. Even when our suffering is comparatively light, we become wound around our thoughts like a dog tied to a pole, running in circles.

The ego is a thin crust floating on the deep, dark ocean of consiousness. From the depths emerge feelings, which our ego interprets primarily through words. The problem with words - and the problem with ego - is that they’re not reality. Our thoughts about suffering are not suffering. These words you’re reading about grief are not grief itself. What I admire about Uncle Iroh is that he refuses to be narrowed or turned inward by his grief. He takes time alone, of course, but he is open to the world, attuned to it as he walks around Ba-Sing Seh.

As I’ve written about before, suffering can open us to largeness of life. The west, with our adulation of rational thought, can stray into relentless talk and treatment. I think men - myself included - are often guilty of intellectualising our sadness, rather than using it to access their world in a richer, meaningful ways. Thinking about sadness, we become sadness. Eastern philosophy reminds us this need not be so. As Alan Watts, inspired by the Hindu Vedanta, wrote:

“We do not ‘come into’ this world. We come out of it, as leaves from a tree. As the ocean ‘waves’, the universe ‘peoples’. Every individual is an expression of the whole realm of nature.”

The ego tricks us into thinking we’re separate containers, depression reifying the disconnection. But it’s an illusion, a game we’re playing through the prism of language. Instead, we are all expressions of the same universe, winking at each other. And because you cannot ‘own’ the molecules, atoms, cells and processes that make you, you also cannot ‘own’ your suffering - it is simply an expression of the universe arising and passing through you. Mercifully, ultimately, you are in fact not your sadness.

Even if the ego is an illusion, the suffering is still real. Uncle Iroh never denies this. At his son’s shrine, he allows the sadness to flow and move through him. It is what he has done with his suffering that causes this inflexion of heartbreak. Iroh elects to channel his suffering into being a father figure for young men of Ba-Sing Seh - the playful caterwauling, his sage advice - and in the process transforming deranging grief into connection and growth. His grief transcends the container, allowing Iroh to connect with the world around him in a moment of profound disconnection. His grief connects him closer to life.

For in each of the young men Iroh helps, he sees the same fragment of humanity he saw in his son. For most of his day he pays respect to his son’s birthday by honoring the thread that connects us all. As his song goes

“Leaves from the vine

Falling so slow

Like fragile tiny shells

Drifting in the foam.”

Just as we emerge out of the universe and slowly fall, we exist in the froth of cosmic space as hollow, fragile shells filled from time to time with sadness and grief. Just as the shells are indistinguishable from the shores on which they lie, so we are fragments wandering on top of the universe, shuddering with its immensity.

And so Iroh remembers his grief is not his alone; consequentially, the manner in which he channels it toward his fellow men matters a great deal indeed.

“Little soldier boy

Come marching home

Brave solider boy

Comes marching home.”

Share this post